How Bitcoin Works

Topics

Blockchain Introduction

The root problem with conventional currency is all the trust that’s required to make it work. The central bank must be trusted not to debase the currency, but the history of fiat currencies is full of breaches of that trust.

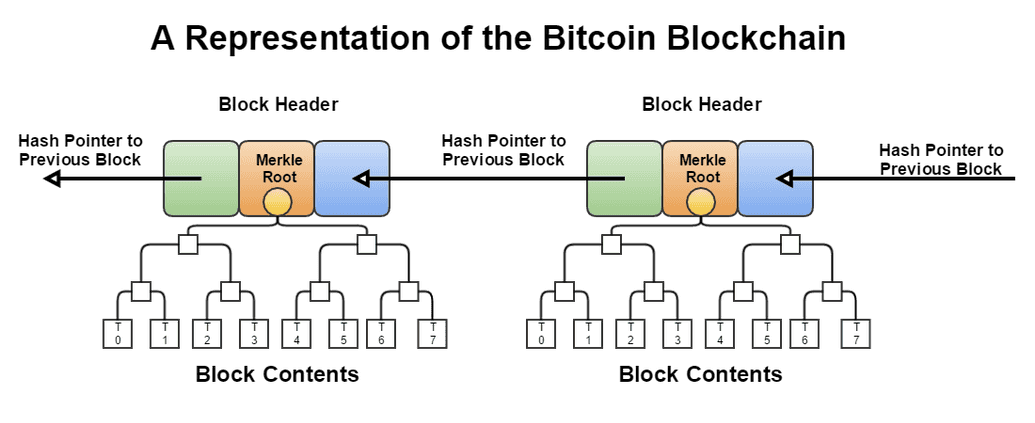

The name "blockchain" is a bit of a misnomer. A blockchain is a collection of blocks, each of which contains a transaction. The first block is called the genesis block, and it is followed by a serties of sequential, immutable, chronological blocks.

Each block contains the ledger of all transactions that have happened in the interval between the previous block and the current block.

The genesis block is said to have a block height of zero, as no blocks precede it in the blockchain. Thereafter, each block is said to have a block height of one higher than the previous block. In other words, the block height can be derived from taking the current length of the blockchain minus one.

All transactions on the Bitcoin protocol are grouped into blocks on an approximately 10 minute interval. The block is then broadcasted to the network. Considering the volume of transactions in a block (~ 10 mins), Bitcoin doesn't actually transmit a full record of all transactions in a block, but rather include the Merkle root of that block's transactions in its header ("block header"). Full nodes participants can however obtain the full transactions in a block by sending a separate request.

We've learned in earlier modules (Cryptography in Blockchain) that because the Merkle root is a cryptographic accumulator over all transactions in a block, it is possible for any node to verify the integrity of a block -- or inclusion of a transaction -- by verifying the Merkle root.

As illustrated above, every block has a header, which includes a hash of the previous block, This in effect creates a "block chain" that start at the genesis block up to the most recent block. A block chain also has the guarantee of being chronological and continuous because the previous block's hash required in the header would otherwise be unknown.

A security feature of the block chain is that it is computationally infeasible to forge or modify a block once it has been included in the chain because the blocks that follow it will have to be re-computed. Exactly why it is computationally infeasible is elaborated later under the Proof of Work section, but the key idea is a block is accepted when the participant ("miner") has solved a cryptographic puzzle ("proof of work") to generate the block's header. This activity is called "mining" and simply refers to the process of finding a valid block header, i.e solving the cryptographic puzzle.

Before we delve into Proof of Work, let us take a deeper look at what makes up a block header in the original Bitcoin protocol as conceptualized by Satoshi Nakamoto.

Block Header

A block header contains the following fields:

- Version: The version of the block header.

- Previous Block Hash (

hashPrevBlock): The hash of the previous block in the chain. - Merkle Root (

hashMerkleRoot): The Merkle root of the transactions in the block. - Timestamp (

nTime): The time the block was created. - Difficulty Target: The target difficulty of the block.

- Nonce: The number of times a hash is tried before it is accepted.

Version

Upgrades to the Bitcoin protocol are made through a mechanism described in BIP 34. It is proposed as a mean for the bitcoin network to collectively consents to an upgrade to the protocol, which includes making changes to the block binary structures, rules, behaviors, and other parameters.

- Genesis blockVersion 1 was introduced in the genesis block in January 2009. Last version 1 block is block number 227,835 (24th March 2013)

- Bitcoin Core 0.7.0 (September 2012)As described in BIP34, valid Version 2 blocks require the current block's height to be encoded into the first bytes of the coinbase field.

- Bitcoin Core 0.10.0 (February 2015)As described in BIP66, valid blocks now require strict DER encoding of all ECDSA signatures

- Bitcoin Core 0.11.2 (November 2015)Specified in BIP65, blocks now support the new `OP_CHECKLOCKTIMEVERIFY` opcode.

Block headers include the version field to indicate which set of block validation rules to follow.

Previous Block Hash

This is a SHA256(SHA256()) hash (in internal byte order) of the previous block's header.

This ensures that no previous blocks can be tampered with since changes to the previous block's header would invalidate the current block.

Merkle Root Hash

This is a SHA256(SHA256()) hash (in internal byte order) of the transactions in the block. This ensures that not even a

single transaction can be tampered with since changes to the transactions would invalidate the current block.

Read more in Cryptography in Blockchain.

Timestamp

Specified as nTime, this refers to the Unix timestamp as seconds since 1970-01-01T00:00:00 (UTC).

It is the block time when the miner started hashing the header and finding the nonce.

Full nodes will not accept blocks with headers more than two hours in the future according to their clock.

Target

The target (nBit) is a 256-bit (extremely large) number; the lower the number is the harder it is to find a hash that is below the target. This is because the SHA-256(SHA256()) function of a block header

must be lower than or equal to the current target for the block to be accepted by the network.

Metaphorically, block generation is akin to a lottery and not a long, set problem (eg. doing a million hashes iteratively). Each time you hash, you are getting a random number between 0 and the maximum value of a 256-bit number (2^256) known as the target. If your hash is below the target, you win the lottery and the block is accepted. If it is not, you increment the nonce (completely changing the hash) and try again. The main idea being that there exist some combination(s) of hash and nonce that will result in a hash below the target.

Since the difficulty of finding a hash below the target is proportional to the target, we can use this property to control for the proof-of-work difficulty. With the aim of producing one block every 10 minutes, the network regularly (every 2016 blocks, ~2 weeks) updates the target by comparing the actual time it took in block generation to the target time and modify the target by the percentage difference.

This rebalancing of difficulty is capped so a target is never changed by more than a factor of 4 either way You can see the current difficulty target here.

Nonce

An arbitrary number between 0 and 4,294,967,295 miners change in their attempt to produce a hash less than or equal to the target. It starts at 0 and increment by 1 each time a hash is generated. If all 32 bits of the nonce are tested (resulting in a "Nonce overflows"), the miner can either:

- Increment

extraNoncelocated in the coinbase transaction, hence changing the Merkle Root, giving the miner a chance to reset Nonce and try again. - Update

nTimein the block header, hence changing the timestamp, giving the miner a chance to reset Nonce and try again.

Without the nonce mechanism, miners in their search for a hash below the target would have to do a of arbitrary work such as modifying the transaction set (which include recomputing the Merkle Root), change the timestamp, and rehash the entire header. With the nonce parameter, miners can keep all variables constant while varying the nonce value.

In Python, an implementation of the header with all the six fields would look like:

import hashlibfrom binascii import unhexlify, hexlifyheader_hex = (# Block version: 2'02000000' +# Hash of previous block's header'b6ff0b1b1680a2862a30ca44d346d9e8' +'910d334beb48ca0c0000000000000000' +# Merkle root of transactions'9d10aa52ee949386ca9385695f04ede2' +'70dda20810decd12bc9b048aaab31471' +# [Unix time][unix epoch time]: 1415239972'24d95a54' +# Target difficulty (0x1bc330 * 256**(0x18-3))'30c31b18' +# Nonce'fe9f0864')header_bin = unhexlify(header_hex)hash = hashlib.sha256(hashlib.sha256(header_bin).digest()).digest()hexlify(hash).decode("utf-8")# returns:# 2837af674e81436b09e0c937e94d96fe32e5c872391ba1090000000000000000hexlify(hash[::-1]).decode("utf-8")# returns:# '000000000000000009a11b3972c8e532fe964de937c9e0096b43814e67af3728'

For completeness sake, the genesis block (first block of a blockchain) contains the following values in its block header:

hashMerkleRoot = '0x4a5e1e4baab89f3a32518a88c31bc87f618f76673e2cc77ab2127b7afdeda33b'block.nVersion = '01000000'block.nTime = '1231006505'block.nBits = '0x1d00ffff'block.nNonce = '2083236893'# hash of this blockhash = '000000000019d6689c085ae165831e934ff763ae46a2a6c172b3f1b60a8ce26f'

Notice the absence of a reference to the previous block's header. This is because the genesis block has no previous block.

Keep in mind of the nBits field, as we will come back to this number in a later section on the difficulty.

Block generation

The merkle root is a cryptographic accumulator over all transaction ID (TXIDs) of transactions in a block. These TXIDs are preceded by the coinbase transaction, which is the first transaction in the block.

Unlike other transactions, the coinbase transaction has no real inputs -- it is the transaction that pays out the subsidy and fees to the miners that generated the block.

If a block has only one transaction, the TXIDs of those two transactions are concatenated and hashed with SHA256(SHA256()) to produce the merkle root.

Supposed a block has two transactions, B and C, and transaction C spends the output from B, the TXID of B must be placed before the TXID of C. This preserves the linearity when parsing transactions from a block chain. As mentioned above, the coinbase transaction's TXID will always come first (in the diagram, it is A):

Source: developer.bitcoin.org

Just as we've learned in the last module, hashes are performed in internal byte order when they're concatenated together.

If you were to inspect the Bitcoin network with a blockchain explorer, you would see the network processing at a transaction rate per second of somewhere between 3 to 5. You may think of comparing this to the number of blocks say in the last few hours, and wonder if miners are generating blocks too slowly. Would it not be possible for the miner to be generating blocks a lot more frequently by accepting maybe a few transactions at a time and find the nonce that produces a hash below the target, hence earning more reward?

That would have been a fair trade-off for the miner has the difficulty of this proof-of-work been far, far easier. However, since the probability of finding the nonce remains constant whether the miner is performing proof-of-work on a block with 1 transaction or say 2,000 transactions, the miner is incentivized to include more transactions as they receive more mining fees. Transactions that did not make it in the block would remain in the mempool waiting to be included in the next block.

On the topic of block rewards, all blocks with a block height less than 6,930,000 are entitled to receive a block subsidy of newly created bitcoin value, which is recorded in the coinbase transaction.

This reward started at 50 bitcoins and is being halved every 210,000 blocks — amounting to approximately once every four years. As of this writing (January 2022), it's 6.25 bitcoins.

The block reward refers to the sum of transaction fees and block subsidy.

A note on the difficulty

This difficulty is represented as a 256-bit unsigned integer. The header hash must be equal or lower than this

value to be considered valid. However, this field is encoded as nBits which only holds 32 bits, so the target number

is actually converted into a compact version instead of the full 256-bit representation.

The initial difficulty target of the Bitcoin network was 0x1d00ffff (target of 1), equivalent to nBits of 486,604,799 and a full 256-bit of 0x00000000ffff0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000. A target of 1 set the network at the minimum difficulty.

A theoretical maximum difficulty is when the target is 0.

Picking the latest target from the time of writing, we see the difficulty has increased, and now (as of this writing) a header hash is required to be equal to or

lower than a value such as 0x0000000000000000000f4c3a2000000000000000000000000000000000000000, considerably harder than the initial target.

If you use a Hex calculator, you can derive the difficulty through a division . In our examples above, this would result in a decimal of 18,399,468,057,381, or 10bbf5c1f324 in hex.

Referring to the historical chart above, when one look at the Number of Transactions per Block and Network Difficulty graph over the years, one can make the observation that the difficulty has significantly increased over time. In the infancy of the Bitcoin network, the difficulty being much lower than it is now, miners could take a handful of transactions and iterate through the number of nonces from 0 to 4,294,967,295 to find a SHA256(SHA256()) hash that is below the target (the difficulty).

This is much more difficult to do now and miners routinely iterate through the nonce space before deciding that something else needed to be changed in the headers (such as the timestamp) to reset the nonce and iteratively try again. The network's target of a block generation every ~10 minutes lend a dynamism to the difficulty.

Every 2016 blocks (~2 weeks), the target is updated by comparing the actual time it took to generate the block to the target time and modify the target by the percentage difference.

Before we proceed to the next section, spend some time to ponder on the fact that a coinbase transaction ("generation transaction") is included in the merkle root. Recall that this is always the first transaction in a block, created by the miner to record the reward and fees paid to the miner. This in effect means that it is extremely unlikely that two miners will generate the same Merkle root since each miner will have a different Bitcoin address. This reiterate the comparison of bitcoin mining to the lottery problem -- every miner has the same probability of winning as every other miner.

Orphan blocks

On the topic of block generation, another interesting question pertains to the case of forks when two or more blocks are generated within seconds of each other ("accidental forks"). The idea of a blockchain is that the chain is a single, continuous chain of blocks. For any valid block, there can only be one parent block (except the "genesis block") and one child block. Consequently, for any given block there is only one path to the genesis block.

When two blocks are created within seconds of each other, one-block forks are created. If the fork is of equal length, the miners generate blocks onto whichever block that they receive first. As a result, one of the chain would be longer (with the addition of the new block) and this longer chain is considered the "main chain".

Blocks in shorter chains are considered invalid and all valid transactions of the blocks inside the shorter chain are re-added to the queue ("mempool"). These transactions may still be added to the main chain, but they would have to be included in another block.

The mining reward for the shorter chain will not be present in the longest chain.

History on Proof of Work

Bitcoin and many other blockchain protocols use a model called (or largely based on) "proof of work", which requires proof of "computational resources spent" as a mean to discourage illegitimate uses or behaviors.

Consider the problem of email spam. In 1992, Cynthia Dwork and Moni Naor used the term 'pricing function' in their introduction to using computational resources for email spam prevention:

We present a computational technique for combatting junk mail in particular and controlling access to a shared resource in general. The main idea is to require a user to compute a moderately hard, but not intractable, function in order to gain access to the resource, thus preventing frivolous use. To this end we suggest several pricing functions...

- Cynthia Dwork, Moni Naor, Pricing via Processing or Combatting Junk Mail (1992)

A legitimate user is not inhibited but a spammer with hundreds of thousands of recipients would find the computational resources required prohibitively expensive. In 1997, Adam Back proposed a proof-of-work function called Hashcash, which was similar in motivations, but with the novelty of using hash functions as the proof of work.

The idea was simple -- users of a network would be required to compute a hash as proof that "some" computational resources were spent before the email was spent. The Hashcash algorithm by Adam Back requires a considerable amount of computing resources to compute but is easy to verify (that the work was done right). This is a desirable property -- much like what we've learned in the Integer Factorization Problem -- because it allows the recipient to quickly and effortless verify the proof of work before deciding on opening the email. Adam expanded on this protocol later in a paper titled "Hashcash - A denial of service counter-measure", in which he explained the use of a cost / pricing function also present an anti-DOS mechanism since malicious parties are required to "pay" an infeasible amount of computational resources for such an attack.

From: "Satoshi Nakamoto" <satoshi@anonymousspeech.com>Sent: "Friday, August 22, 2008 4:38 PM"To: "Wei Dai" <weidai@ibiblio.org>Cc: "Satoshi Nakamoto" <satoshi@anonymousspeech.com>Subject: "Citation of your b-money page"/*I was very interested to read your b-money page. I'm getting ready torelease a paper that expands on your ideas into a complete working system.Adam Back (hashcash.org) noticed the similarities and pointed me to yoursite.I need to find out the year of publication of your b-money page for thecitation in my paper. It'll look like:[1] W. Dai, "b-money," http://www.weidai.com/bmoney.txt, (2006?).You can download a pre-release draft athttp://www.upload.ae/file/6157/ecash-pdf.html. Feel free to forward it toanyone else you think would be interested.Title: Electronic Cash Without a Trusted Third PartyAbstract: A purely peer-to-peer version of electronic cash would allowonline payments to be sent directly from one party to another without theburdens of going through a financial institution. Digital signaturesoffer part of the solution, but the main benefits are lost if a trustedparty is still required to prevent double-spending. We propose a solutionto the double-spending problem using a peer-to-peer network. The networktimestamps transactions by hashing them into an ongoing chain ofhash-based proof-of-work, forming a record that cannot be changed withoutredoing the proof-of-work. The longest chain not only serves as proof ofthe sequence of events witnessed, but proof that it came from the largestpool of CPU power. As long as honest nodes control the most CPU power onthe network, they can generate the longest chain and outpace anyattackers. The network itself requires minimal structure. Messages arebroadcasted on a best effort basis, and nodes can leave and rejoin thenetwork at will, accepting the longest proof-of-work chain as proof ofwhat happened while they were gone.Satoshi*/

Another email from Satoshi that is of interest was the one on January 10, 2009:

From: Satoshi NakamotoSent: Saturday, January 10, 2009 11:17 AMTo: weidai@weidai.comSubject: Re: Citation of your b-money page/*I wanted to let you know, I just released the full implementation of thepaper I sent you a few months ago, Bitcoin v0.1. Details, download andscreenshots are at www.bitcoin.orgI think it achieves nearly all the goals you set out to solve in yourb-money paper.The system is entirely decentralized, without any server or trustedparties. The network infrastructure can support a full range of escrowtransactions and contracts, but for now the focus is on the basics ofmoney and transactions.There was a discussion of the design on the Cryptography mailing list.Hal Finney gave a good high-level overview:| One thing I might mention is that in many ways bitcoin is two independent| ideas: a way of solving the kinds of problems James lists here, of| creating a globally consistent but decentralized database; and then using| it for a system similar to Wei Dai's b-money (which is referenced in the| paper) but transaction/coin based rather than account based. Solving the| global, massively decentralized database problem is arguably the harder| part, as James emphasizes. The use of proof-of-work as a tool for this| purpose is a novel idea well worth further review IMO.Satoshi*/

These correspondences are interesting in that it shed light on the invention of the "peer-to-peer network" and the contributors behind what would become the "proof-of-work" algorithm that Bitcoin uses.

Hashcash

The original Hashcash algorithm works by requiring a user to compute hashes repeatedly until they find a value that, when hashed with SHA1, produces a digest that starts with a specific number of zeros. The "easily verifiable" property of this algorithm comes from the fact that any human can perform verification that the work has been done correctly by computing the hash of the work using simple, pre-installed command line utilities and counting by eye how many zeros are in the output.

When we expand the concept further, we observe that the difficulty of finding the right value from a scan exponentially increases with the number of leading zero bits required.

Recall from the hashing functions chapter in earlier modules that we have the following properties for hash functions:

- Fixed length: the hash function is fixed-sized, and thus can be used to generate a fixed-length signature.

- Pre-image resistance (One way): the hash function cannot be used to generate a pre-image of the message.

- , where is the message and is the hash. is a pre-image of and cannot be reverse-computed from .

- A full hash inversion is possible, but is computationally infeasible with a complexity of where is the hash size (e.g 256 for SHA-256)

- Second pre-image resistance: Given and , it should be infeasible to find any other message, where

- Also known as weak collision resistance

- Strong collision resistance: Different input message should result in different hash, that is

- It is impossible to fully avoid collisions in hashing functions (compression down to 32 bytes, hence subjected to the same problem as a "birthday function") -- but sufficienctly long collisions are computationally infeasible to find.

Hashcash builds on these security properties, allowing a person to verify cheaply through but very difficult to find the pre-image of . In the context of cryptocurrency mining, a miner thus expend considerable effort to find a value that would hash to the required number of leading zeros, but the other nodes on the network only need to compute said hash to verify that the work was performed correctly.

While we now have a model to prove that some computational resources have been expended, we have yet to "bind" this work to a specific reason. In other words, any other users can reuse the same pre-image and hash to claim that they, too, have performed a proof-of-work. This is why we include a specific service string, s to the hash function, giving this proof-of-work some notion of purposefulness.

When expressed mathematically, this takes the form of:

The miner scans for a value of counter, c, that satisfies the above equation. The service string, s could be a web server domain name, a URL, the email addresses of recipients, or any other string that is unique to the task.

n is the size of the hash output in bits (SHA256 would assign the value of 256 to n), and k is the number of leading zeros required (the "work factor"). A k of 40 would on average require a scan of 1 trillion tries while a k of 20 would require a scan of 1 million tries.

Often, yet another random variable is added to the mix, r, if the service string s is not unique to the miner. The work hence becomes to find so no two miners will find the same proof-of-work (only the first to present it will be rewarded and other would have just done the work for no reward).

In the case of Bitcoin, the service string is the coinbase (first transaction in the block), which includes the miner's address, the block height, the mining reward,

transactions to validate in the block, timestamp and potentially the extraNonce bits. This eliminates the need for a random variable, r, since the miner's address is unique and would serve the

same purpose of avoiding collisions that come with random starting points. As a related aside, miners are expected to use a random reward address for each successful block.

Another way that Bitcoin differs from the original Hashcash proposal is that the original protocol scales its difficulty by adjusting the number of leading zeros in the hash output, which can be expressed with . Since the difficulty is scaled in powers of 2, anyone can measure it by counting the number of leading zeros in the hash output. Bitcoin, on the other hand, requires more control to keep to a ~10-minute block interval, it uses a floating point k value to represent difficulty, giving it more precision.

Finally, it should be noted that the original Hashcash algorithm uses SHA1 because it was first released in 1997 and SHA1 was the standard digest algorithm recommended for use by NIST. Bitcoin, having been released in 2009, uses SHA256, which is a much more secure digest algorithm.

Blockchain Mental Model

- 11

- 22

- 33

- 44

- 55

- 11

- 22

- 33

- 44

- 55

- 11

- 22

- 33

- 44

- 55

The default block difficulty of 2,3 and 4 may take a while to mine.

If this isn't desired or if you're on a limited computer, you can reduce the difficulty by decrementing the numbers above.

For example, setting it to 1,1 and 1 will reduce the time it take to find the nonces to literal seconds.

- Block 0

Fundraising Ledger

Version (4 bytes)

04000000

Merkle Root Hash (32 bytes)

Add a Donation 💰

Unix Epoch Time

6230314a

Difficulty

2

Previous Block Header

0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

Nonce

0

Hash

Hit the Mine ⛏ button or Add a Donation 💰.

- Block 1

Fundraising Ledger

Version (4 bytes)

04000000

Merkle Root Hash (32 bytes)

Add a Donation 💰

Unix Epoch Time

6230314a

Difficulty

3

Previous Block Header

Hit the Mine ⛏ button or Add a Donation 💰.

Nonce

0

Hash

Hit the Mine ⛏ button or Add a Donation 💰.

- Block 2

Fundraising Ledger

Version (4 bytes)

04000000

Merkle Root Hash (32 bytes)

Add a Donation 💰

Unix Epoch Time

6230314a

Difficulty

4

Previous Block Header

Hit the Mine ⛏ button or Add a Donation 💰.

Nonce

0

Hash

Hit the Mine ⛏ button or Add a Donation 💰.

A small disclaimer here is that I've simplied the Difficulty representation to a single integer, but

in the original Bitcoin protocol, this is a 32-bit unsigned integer. When we adjust the difficulty from

120 (decimal) to 60 (decimal), we operate on the binary level, which is to say we narrow down the

qualifying range of values from 0111 1000 (120) to 0011 1100 (60). You can read more of this in the

previous section discussing the difficulty (nBits) field.

The equivalent of the current difficulty level of Bitcoin mining would be closer to finding a nonce that yields a hash with 17-20 leading zeroes where in this example we only used 4 leading zeroes to reduce the computational resources required.

As we add new fundraising records to the blockchain, observe that the record is practically immutable as any alterations to the record will nullify the resulting proof-of-work and all subsequent blocks. As a user, one need only to compare the hashes between the obtained and what was broadcasted to the network to have practically full certainty that the records were not altered or tampered with.

Similarly, the mechanism of allowing two or more peers to directly compare hashes allow the node participants to have practically full certainty that the records were not tampered with, without sequentially scanning every transactions ever recorded in the blockchain. A malicious node may still try to temper with our fundraising ledger, but the actor will now have to:

- Find the right nonce for the block, and all subsequent blocks

- Gain 51% of the total network hashrate to be able to validate the block ("51% attack")

As blocks are added ~10 minutes and the network hashrate is ~219 quintillion (18 zeros) hashes per second (as of this writing, block height 719,609), this is a monumental task to be performed by anyone, even with the most powerful machines in the world. Furthermore, this would also mean that the attacker will have obtained such enormous computational resources that their mining speed exceed the speed of all the remaining participants combined. Even setting aside the near-impossible feat of acquiring such computational resources, there is still the question of incentives. The participant, if they should exist, would have strong incentives to maintain the longevity of its blockchain, such that the value of the mining rewards would be greater than the value of such maintenance and upkeep.

If you find the Unix epoch time representation in the above blockchain confusing, try experimenting with it in the following code snippet:

For experimentation purposes, you may also want to generate random hexadecimal characters or Unix Epoch time using common built-in tools on your machine:

# returns decimal Unix Epoch time# example: 1642154966date +%s## returns hexadecimal Unix Epoch time# example: 61e14e6adate +%s | xargs printf '%x\n'# 16 random hexadecimal charactershexdump -n 16 -e '4/4 "%08X" 1 "\n"' /dev/urandom

Coinbase Transaction

To further solidify the concepts, I recommend that you use blockchain explorer and look for the latest (most recently mined) blocks. For example, the most recently mined block as of this writing would be Block 721031, mined on January 30, 2022.

The blockchain explorer will prominently display the hash of the block, the block height, the number of transactions in the block, the miner and the block header fields described above. Block 721031 has a block reward of 6.25 BTC, which is easy to understand.

Since block reward starts at 50 and halves every 210,000 blocks, a simple floor division will yield 3 halvings:

In addition to the block reward of 6.25 BTC, block #721031 also includes the fee reward of 0.00064084 BTC, which is the sum of transaction fees rewarded to the miner for calculating the hash for this block.

In this block, the first transaction (coinbase transaction) is hence a miner's reward transaction, where the payout of 6.25 BTC + 0.00064084 BTC to the miner's address is recorded.

Peer-to-peer Network

With the right incentives in place, the blockchain can now be maintained by a peer-to-peer network of nodes. But what makes a great peer-to-peer network?

With Bitcoin, anybody can download a piece of software that can be used to create a node, and then connect to the Bitcoin network, whether the intention is to validate blocks ("mining"), or to participate in transactions, or simple to observe and audit the blockchain. This is what gives Bitcoin the property of being truly decentralized, in that the network is not controlled by a single entity but by anyone who wants to participate.

The fact that Bitcoin is a truly decentralized network also means that it is resilient to attacks or any kind of malicious activity. The impact of any single compromised node is easily mitigated by the network, and this network cannot easily be "taken down" by a centralized entity since the network comprises of many, geographically diverse independent nodes. Each node in essence stores a history of all transactions ever recorded in the blockchain, and so long as there is one node somewhere, the network is able to validate the authenticity of any transaction. Any node that attempts to act maliciously will quickly be detected since its hashes will be different and will not be accepted by the network.

Users in this network can transact by sending bitcoins, and they do so by broadcasting digitally signed messages to the network using the Bitcoin protocol. Using ECDSA, the sender signs the message with their private key, and node participants can verify the signature with the public key of the sender. Once the signature is verified, the message is accepted by the network and bitcoin miners will perform the proof to work to validate this transaction and include it into the ledger.

Knowledge Check

Practical Exercises

Inspect block 500000 in any blockchain explorer to answer question (1) to (3).

What is the number of transactions in this block?

What is the sum of block reward and fee reward?

Block Reward BTC: Fee Reward BTC: Sum (Total BTC):Inspect the miner responsible for block #500000. In the coinbase transaction of this block, how many bitcoins are transferred and to whom? Paste the full address into the answer field. Do not perform any rounding to the transaction amount.

Output Address:Output Amount BTC:What is the

hashMerkleRootfield referring to in Bitcoin mining?Supposed the miner has exhausted all possible bits of the nonce, what can be done to reset the nonce and try again?

Pick all that apply.When an accidental fork occur from two or more miners finding a block within seconds of each other, how is this fork resolved?

What is the search space for the nonce?

Learning Modules

Learning Modules